Text Size

Search Articles

More By This Author

- Holy Communion.

- Trinity Sunday and a Trinity Icon

- Social Justice Sunday 2009

- Bulletin 19.7.09

- Trinity Sunday : What's so special about the Trinity?

- ...all 9 articles

More From This Category

- God of the Second Chance.

- From a hospital bed.

- What makes Shiners Shine?

- The precious wholeness of things.

- So what do you see?

- ...all 56 articles

Article Information

- Added June 10th, 2010

- Filed under 'Sermons'

- One attached file (jpg, 746kb).

- Viewed 4406 times

Trinity Sunday and a Trinity Icon

By Stuart Grant in Sermons

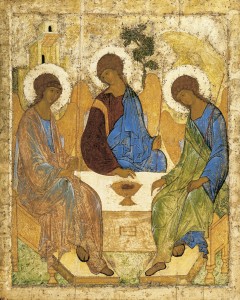

Stuart based his Trinity sermon on the Icon painted by Andrei Rublev.

You will no doubt be wondering about this strange picture that I've placed here in the sanctuary of the church.It's not actually a picture; it's an icon. And those of you who have some idea of what an icon is may be wondering why, in a Methodist worship service, we should be focussing out attention on it. Icons are not a Methodist thing; they are part, and a very strong part, of the spirituality of the Eastern Orthodox churches, the biggest branch of the Christian Church next to Roman Catholicism. Some of you may remember, as part of our Open Education programme three or four years ago, how we visited the little Orthodox Church in South Dunedin. There Father Ilyan Eades, sadly no longer with us, explained the worship of the church. One thing I recall very vividly was how the walls of the church were covered in icons.

The word "iconic" in recent years has become so overworked as to be a rather tiresome expression. It's used in tourist brochures to refer to some extra special feature of a landscape, or of some very special building. But what in fact IS an icon?

It's not just a picture. It is a work of religious art and it attempts to create a kind of window from everyday life into the world of the divine. It is an attempt to get across a particular spiritual truth or truths by visual means. That's perhaps not easy for people like us. We are so used to receiving spiritual truth by means of words, in the form of readings, sermons and spoken or read prayers, - with the help of music as well. Religious pictures are not a usual part of our worship experience.

This particular icon is probably the most famous of all. It was painted somewhere between 1410 and 1420 by a Russian monk, Andrei Rublev. And it is often referred to as the Old Testament Trinity. That's why I've chosen to use it in our worship on this Trinity Sunday. It has to be said that the idea of the Trinity dated from New Testament times, so to speak of an "Old Testament Trinity" is rather curious. An examination of the reading from Genesis gives us the explanation why Christians in far off times felt it was possible to detect a reference to the Trinity in this story.

Abraham is sitting at the door of his tent by the oaks of Mamre when three mysterious visitors appear. In the spirit of true eastern hospitality, Abraham runs to meet them, but strangely he addresses the three not as "My lords" but in the singular, "my lord".

So Christians came to the conclusion that Abraham was talking to God as Trinity.

This is what Rublev took as the subject of his icon, and in doing so he attempted to paint what could really not be painted.

This icon of the Old Testament Trinity has a very strong personal significance for Cornelia and me. It was given to us as a wedding present, and it has hung on the living room walls of every parsonage we've occupied since we were married. I must confess, however, that in all those years it's been more just part of the furniture than an object of spiritual contemplation. But let me explain how we came to receive it.

When she was a theological student in Germany, Cornelia together with her mother belonged to an organization called "Philoxenia"; (that's a Greek word meaning "love of the stranger"). The members of Philoxenia came from Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches and they used to meet from time to time for worship and study, sharing the riches of their respective heritages. A strong point among them was hospitality, and so they adopted this icon, which was inspired by the story of Abraham offering hospitality to the three mysterious visitors, as their symbol.

And it was through their commitment to hospitality that Cornelia and her mother invited two strangers, international students at the Ecumenical Institute of the World Council of Churches near Geneva to their home at Christmas 1980. One of the strangers was a New Zealander, - this New Zealander. But that's another story.

The secretary of Philoxenia was a lady called Ilse Friedeberg, who was for many years a simultaneous translator for the World Council of Churches in Geneva. She was invited to our wedding, and as her gift she brought with her this icon.

Now let's look at the icon itself. We see three figures, - depicted as angels, seated around a table. If you look closely at the faces, you'll see that they're all the same, and the eyes of each figure seem to be looking at the other in respectful kind of way, as if each is deferring to the other. If you look at each one in turn, you get the sense of a circular motion, which affirms the essential unity of the scene and of the three figures: Trinity; three in one.

There is a variety of opinion as to which figure is meant to represent which person of the Trinity: which is God the Father, which is the Son, and which the Holy Spirit.

The clues to this come from their clothing.

Each one is wearing blue, the colour of the sky. In religious art this represents the divine. But each one is wearing clothing of another colour as well, and it's here that we're able to discern the differences.

The figure on the right is also wearing green, the colour of growth and new life. This is the Holy Spirit. And note that the figure is touching the table; this signifies the earthing of God though the Spirit. Last Sunday we celebrated Pentecost, traditionally the day when the Holy Spirit was poured out on the first Christians. It is through the Spirit that we are made aware of God. And the Spirit is alive and active in God's creation, - as in the opening chapter of Genesis: The Spirit, or breath, or wind of God moves across the waters.

The figure on the right looks towards the figure in the middle, seated in the dominant position behind the table. This figure wears brown, the colour of the earth, along with the blue of divinity, and a gold sash, - the symbol of Kingship. This is the Christ, in traditional Christian belief both divine and human; his two fingers resting on the table stand for these two natures. They also point to the chalice in the centre of the table, which represents his self-giving on the cross.

Christ's gaze is directed to the figure on our left, who also wears the blue of divinity. But this blue is covered with a robe of shimmering gold that seems also partly transparent. It's hard to describe in words, and that no doubt is what Rublev was trying to convey: the impossibility of containing God in words, or pictures, or in any way at all.

The Father is looking forward, raising his hand in blessing to the Son, and at the same time looking down at the chalice, symbol of the self giving of Christ - as if saying, "This is my beloved Son listen to him".

And the hand of the Son, in turn, points around the circle toward the Spirit, on the left. So we see life flowing clockwise around the circle, - from God the Father - Creator to the Son and on to the Spirit. The empty space at the table in the centre completes the picture; it is for us, for you and me. We are invited to complete the picture, to join the circle; we are invited to share in the hospitality God offers us, and take our place at the table.

There is much more symbolism in the icon that we could have considered, - rather too much for the time we have. Though I've tried to describe what I think are the most important aspects of this most famous of all icons.

Probably the most important thought Rublev wanted to get across when he painted the icon was the central place of love: love based on mutual trust. Old texts about the Trinity talk about the Trinity of Love, about the love that fills the Trinity. Most of us aren't familiar with the contemplation of icons. As I said earlier, we are more use to using words. But if we do seriously use this icon as an object of contemplation, we will come to understand and experience the importance of its circle of trust and love.

Henri Nouwen, a Dutch priest who through his writings helped many to a deeper and very practical spiritual life wrote as follows:

"Through the contemplation of this icon we come to see with our inner eyes that all engagements in this world can only bear fruit when they take place within this divine circle . . .we can be involved in struggles for justice and in actions for peace. We can be part of the ambiguities of family and community life. We can study, teach, write and hold a regular job. We can do all of this without ever having to leave the house of love."

In a world so divided by strife and unrest, by growing individualism, by greed, by the gap between rich and poor, we are invited to remain secure within the circle of divine love, and share the strength of that love with those around us.

-- Stuart Grant.